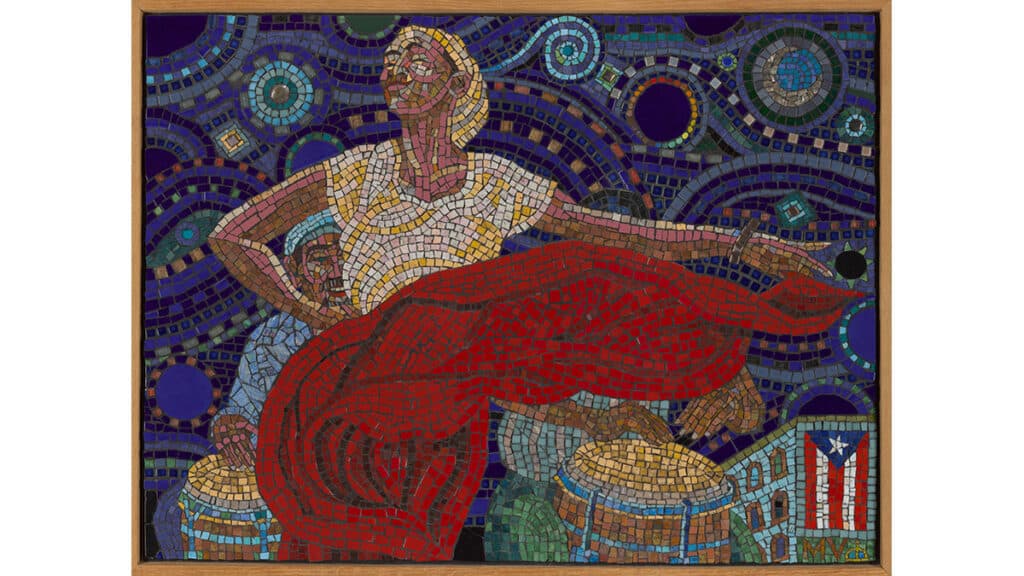

Byzantine Bembé, New York by Manny Vega, is an exhibition of the New York Puerto Rican artist’s wonderful mosaics from the streets of Manhattan’s “El Barrio” East Harlem.

Byzantine Bembé, New York by Manny Vega

Byzantine Bembé, New York by Manny Vega, an exhibition of the New York Puerto Rican artist’s mosaics from the streets of Manhattan’s “El Barrio,” and Yoruba art; is at the Museum of the City of New York in “El Barrio” East Harlem; opening Friday, December 8, 2023. 🇵🇷 🇧🇷

For tickets and more information, visit mcny.org

The key image is of a Puerto Rican bomba dancer. In bomba, the dancer plays a flirting game with the lead drummer, in which the drummer follows the dancer’s movements.

Bomba is an Afro-Puerto Rican tradition that has become a symbol of Puerto Rican identity, for all young Puerto Ricans. Back in the day, in El Barrio and The Bronx, the drum never stopped.

Byzantine Hip-Hop

Walking around “El Barrio” East Harlem, you may notice beautiful mosaic art on street walls, subway stations, cultural centers, and business facades. Many of these are the work of Manny Vega. You can see his work all over “El Barrio” East Harlem; at Pregones Theater in Concourse, The Bronx; and the 110th Street subway station (at Lexington).

Vega calls his work “Byzantine Hip-Hop.” He uses classic Byzantine mosaic techniques of the ancient Greeks, Romans, Turks and other cultures of the eastern Mediterranean. Such work is so treasured that discoveries of ancient Byzantine mosaics often make the international news.

But in Puerto Rico and the Americas we have our own unique histories and art histories. Like El Barrio, El Bronx, New York City and the United States, we are a mix of many peoples and cultures: Indigenous, European, African, and Asian too. We are mixed together, but in some places Indigenous traditions stand out, and in others African Diaspora traditions stand out.

So Vega uses Byzantine mosaic techniques to tell stories of the African Diaspora.

Indigenous Art

Indigenous traditions are important to Puerto Ricans. We are descended from the Taíno and Carib, and though the tribes were absorbed long ago, tribal traditions live on in the lives of the people ~ even today.

Indigenous art is not representative like European art. It embodies spiritual energy, so images of a God, are not just images, they are literally part of God. For us, God isn’t only in heaven, God is in all creation, above, below, everywhere.

Indigenous Taíno petroglyphs in Puerto Rico are stunningly, beautiful. In fact, the famous image of Puerto Rico’s coqui singing frog comes from a Taíno petroglyph on La Piedra Escrita in Jajuya, Puerto Rico. Perhaps we should look at Vega’s art with the same eye.

Yoruba Traditions

Vega is a spiritual man in the Brazilian Yoruba tradition. In Puerto Rico, we tend towards Cuban Yoruba traditions, but it’s all related.

The Yoruba are a people of modern Nigeria, Benin, and Togo who have highly developed cultural and religious traditions. They are one of the three main African Diaspora cultural complexes that rooted in the Americas: Dahomey in Haiti and New Orleans, Yoruba in Cuba and Puerto Rico, and Kongo in Cuba, Brazil, and pretty much everywhere.

- Dahomey traditions became secular Haitian meríngue, and then Dominican merengue.

- Yoruba traditions became secular Latin jazz, and Cuban and Puerto Rican salsa.

- Kongo traditions became Brazilian Candomblé, secular samba, and bossa nova; and then Uruguayan candombé, Argentine milonga and tango.

But we are mixed together in the Americas, and Yoruba traditions have mostly absorbed the other traditions. Most Americans know the traditions through the Cuban Yoruba expressions. Nowadays, we tend to call the whole thing Yoruba.

Yoruba traditions have even entered American popular culture. Br’er Rabbit and Bugs Bunny are both based on Yoruba stories.

Bembé Can be a Ritual or a Party

“Bembé” is a West African word for a community gathering that can be religious, or just a party. In many Indigenous and African Diaspora traditions, dance is how we pray. There are specific rhythms and movements for particular orishas (similar to saints), so we drum, sing, and dance for our orishas in the same way that religious Italians might chant or sing the “Ave Maria.”

If it’s a religious gathering, one of the things that can happen is spiritual possession. In the Caribbean and Latin America, to be spiritually possessed is not a bad thing. It’s a sign of honor, that God considers you worthy of a direct connection. In Spanish flamenco, it’s called “duende.” In Silicon Valley, it’s called flow. When you are in the flow, you can often do things that are beyond your normal abilities. It’s a gift from God.

Vega works inside the spirit of his community. That is his gift. He also does religious mosaics in the Yoruba tradition. His images of Changó; the orisha of musicians, drumming, and dancing; are spectacular.

Changó was a historical character, a king who greatly expanded the Oyo Kingdom, one of the mightiest Yoruba kingdoms. In the same way that Christian saints are deified for their good deeds, Changó was deified for what he did for his people.

Signs of Changó included red and white beads, and the double-headed ax. As the virile male, he is a very popular saint, although you don’t choose your saint, they choose you. Changó is the creator of Cuba’s sacred batá drum. It is double-headed like his ax.

By the way, Changó’s Cuban festival day was a few days before the opening of this exhibition. Friday is his day of the week, and this exhibition opens on a Friday. ¡Maferefún Changó!

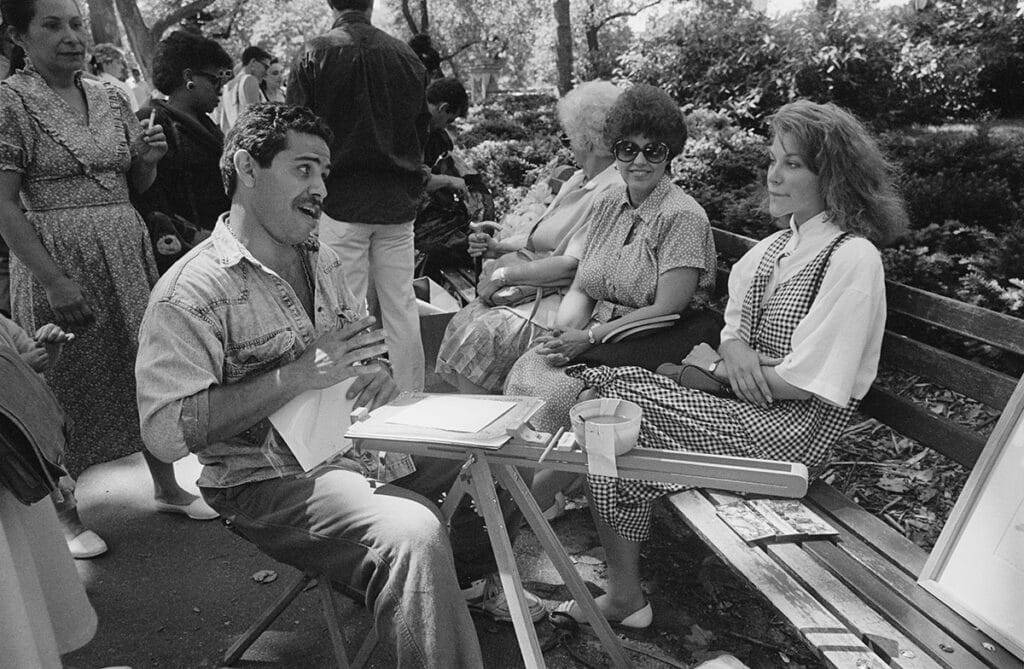

Manny Vega

Manny Vega is a New York Puerto Rican mosaic artist, with Brazilian Yoruba spirituality, who was born in The Bronx in 1956. He has a studio in “El Barrio.”

He learned his craft at Taller Boricua, as a student of master printmaker Robert Blackburn.

Vega is a member of an Afro Brazilian religion in Bahia, Brazil’s cultural heartland. In his religious community, Vega designs ritual costumes and accessories. The African Diaspora tradition in Bahia is Candomblé, but most Americans don’t know what that is, so we just call it Yoruba. Some festival dates and traditions are distinct, but the African Diaspora religions are very similar. In fact all human religions are very similar.

Some of Vega’s religious art is documented in museums at The Smithsonian, UCLA, and Dartmouth College. Books about his work include: “Beads, Body, and Soul: Art and Light in the Yoruba Universe,” and “The Yoruba Artist.”

He also designs costumes and sets for dance and theater. He has designed sets for “La Casita” festival of spoken word at Lincoln Center and Pregones/PRTT in The Bronx.

Vega teaches at El Museo del Barrio, the Guggenheim Museum, American Museum of Natural History, and the CCCADI ~ Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute.

Follow the artist on Instagram @mannyvega.nyc

Àṣẹ